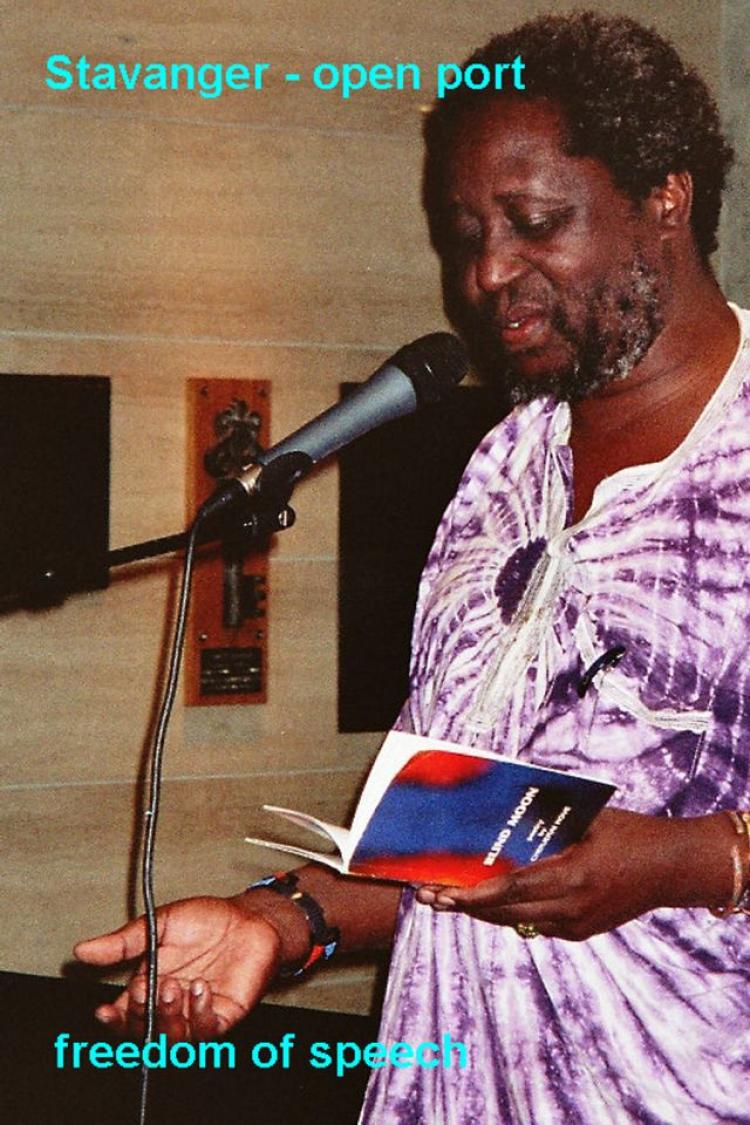

SPRING 07 Featured Writer: Chenjerai Hove

In Chenjerai Hove's essay collection Palaver Finish, he writes that he "loves buses". But when he fled his homeland, what he calls his "cruel, beloved country", it wasn't a bus that took him away. It was a plane. A "ten-day trip" to London began 6 long years of exile. And he's still in exile.

Born into a large family, in Mazvihwa, Zimbabwe, Chenjerai Hove describes his childhood as one filled with happiness and with sadness. Hove's father was a regional king, exercising power over the community in trials and the family in the homes. Homes. Hove's father had several wives, despite the disapproval of the Swedish missionaries. Hove considers himself lucky to have so many mothers, a large, loving family.

Hove remembers his father describing a meeting with the District Commissioner:

. . . having tea, writing documents, retrieving files. Tea became a symbol of power, alongside the pen. . . That was power. The power of tea and pen, the power of office, and the power of language and translators. . . It was taken for granted that this power belonged to the white man.

Hove's education didn't include African literature, the expression "African Writer" wasn't even used. It wasn't until his last year of college that he was introduced to the work of Toby Moyana.

When the Liberation War came, Hove was teaching school, teaching the children English.

. . . most people wonder why the liberation war is so important as a literary event during the de-colonisation process. The war gave us a new experience and we had to search for a new language with which to name things.

Although prior to 1980 few black Zimbabweans were published within the country, after the war this literature blossomed. The poetry anthology And Now the Poets Speak was published, Hove's poems included.

Good or bad English, it did not matter. The language had been harnessed for our own use. It was ours to use as we wanted. It was not a foreign language any more.

However, independence did not bring harmony to the country. The new order of government censored writers.

In 1987 Hove wrote a novel in his mother tongue Shona that addressed women's rights in modern Zimbabwe. Masimba Avanhu (Is This People's Power?) in response to the people arrested for staging a strike that protested the continuation of colonial salary structures. Women were viewed as minor dependants of their husbands.

This novel, and the others that followed, drew the government's attention to Hove. His house was broken into and his computers and discs stolen. His family was threatened and he was under constant surveillance by the police.

In Zimbabwe journalists and other representatives of the media are required to apply for licences from the Media and Information Commission, and the law allows government agents access to manuscripts prior to publication.

Hove wrote a play Sister, Sing Again Some Day, which protested the practice of arresting women who were outside their homes after dark. The play was rejected by the Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation, but Hove travelled to London to help in the BBC radio production there.

Hove describes how the government of Zimbabwe defines creative work and achievements:

An African writer, a haunted poet from a west African country, had told me. . . he feared the minister of information who has the tendency to think that writers are his unpaid public relations officers.

When I won a human rights prize, the German-Afrika Prize, for human rights and freedom, the only complement the government gave me was to send a secret service agent to collect my acceptance speech for their files.

In 2001, the award-winning novelist and poet was threatened by police officers. A car he had sold years before had been found on the border, filled with cannabis. Hove felt it was a matter of time before he'd be framed for a serious crime. He felt that, to make a difference in his country, he'd have to leave his homeland:

When I take up my pen to write, I feel the strength of standing up and refusing to be silent. In an oppressive situation, silence is death.

Chenjerai Hove's Letter to My Mother

Printable file for Hove's biography and Letter to My Mother

© 2007 ICORN, babel

Writers

Latest news

-

23.04.24

-

18.04.24

-

04.04.24

-

26.03.24

-

21.03.24